Part of my intention with the_slow_times is to shine a light on scientific articles that, for one reason or another, may not break into the realm of the casually climate aware. And while I’ll try to sample some of the most current publications, in keeping with the slow ethos, I believe there is merit looking to the recent past.

As consumers of scientific literature, it can be all too easy for the impact of a recent article to hit like a load of bricks only to be washed away in the stream of ensuing news. But, if we take the time to sample from the decade, we can begin to see just how conventional some calls for drastic action really are.

One such paper was published six years ago in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene” is considered by many to be one of the most consequential papers in climate science. Although intriguing, in typical fashion of most peer-reviewed articles, the title doesn’t give much away. But, after circulating, it came to be known by another name: the “Hothouse Earth” paper.

Let’s break it down

It turns out we don’t live on Earth as much as we live within an Earth system. The authors of the paper make the case that the planet we call Earth is made up of a myriad of systems that function in harmony to facilitate life. But, like any choir, harmony isn’t guaranteed.

The authors begin by acknowledging the debate as to whether or not the significance of human impacts on the planet warrant designating our moment as the Anthropocene as distinct from the Holocene — the geologic period that initially gave rise to a flourishing humanity with the advent of agriculture up through the industrial revolution. Regardless of the outcome of this semantic debate, the authors make a simple claim: “The sum total of human impacts on the system needs to be taken into account for analyzing future trajectories of the Earth System.”

Providing framing from their investigation, they lay out four questions:

Is there a planetary threshold that, if crossed, Earth will only continue to get hotter?

If so, what is that threshold?

What would that mean for humanity?

What might we do to avoid said trajectory?

Hothouse Earth Pathway

Considering questions 1 and 2, the paper primarily focuses on what are known as feedback loops. Described as either positive or negative, the terminology is somewhat counterintuitive and can be a little confusing. Positive and negative are not necessarily equated with “good” or “bad.” As they relate to Earth systems, negative feedback loops maintain a given state. Conversely, positive feedback loops amplify or fuel a shift from one state to another. And considering positive feedback loops that increase global temperature or sea level rise, we would be keen to avoid exacerbating them.

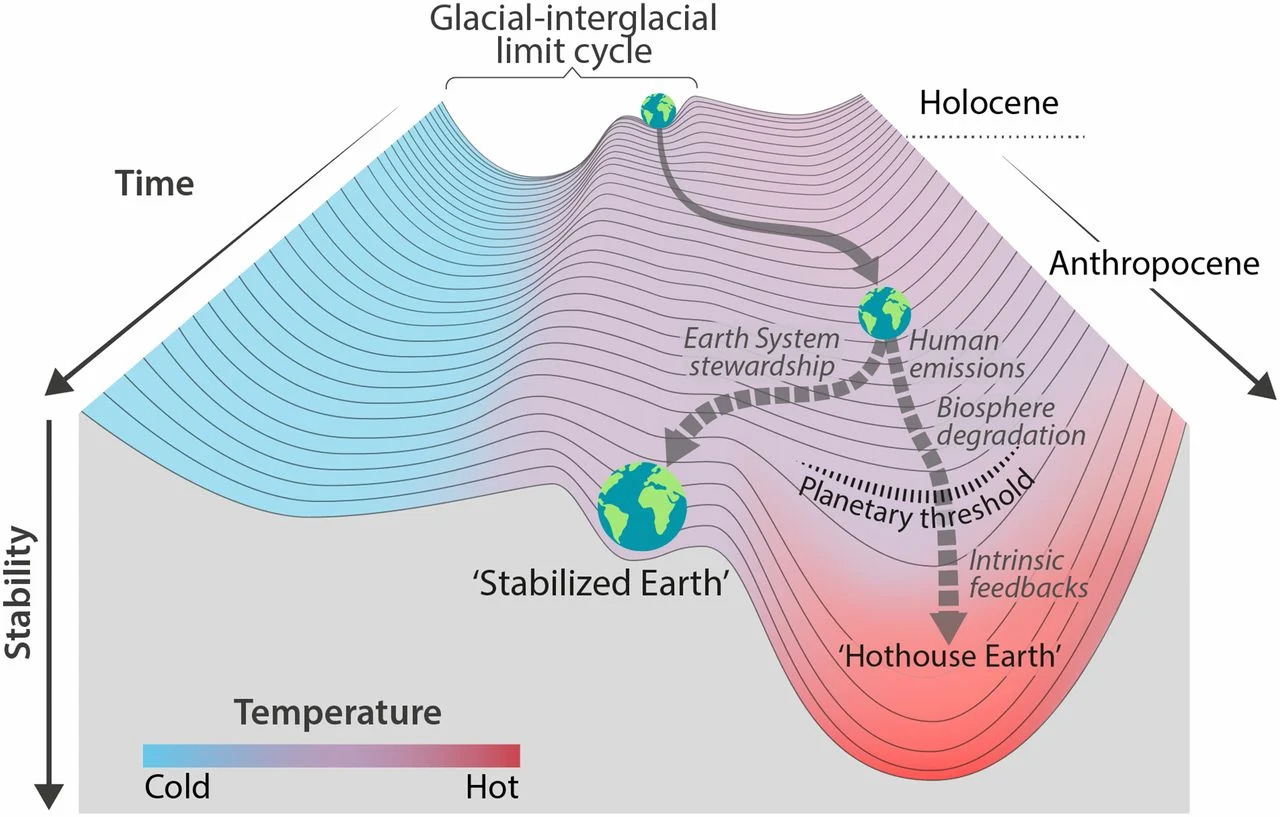

When addressing global temperature rise, the paper uses the conventional baseline of preindustrial levels and discusses rise in relation to the 1.5°C to 2°C targets set by the Paris Climate Agreement. The authors then point out, before factoring in any downstream impacts of feedback loops, a temperature of ~1°C back in 2018 was already fast approaching the known upper limit of the interglacial period of the past million or so years. Suggesting “the Earth System may already have passed one “fork in the road” of potential pathways, a bifurcation (near A in Fig. 1) taking the Earth System out of the next glaciation cycle.”

Dire as these implications could be, it’s important to recognize there exists an element of agency within most feedback loops. That is to say, there are variables within our control that determine the rate of acceleration. But the authors also caution “a domino-like cascade […] could take the Earth System to even higher temperatures” if we hit tipping points. A point at which feedback behaviors become self-perpetuating.

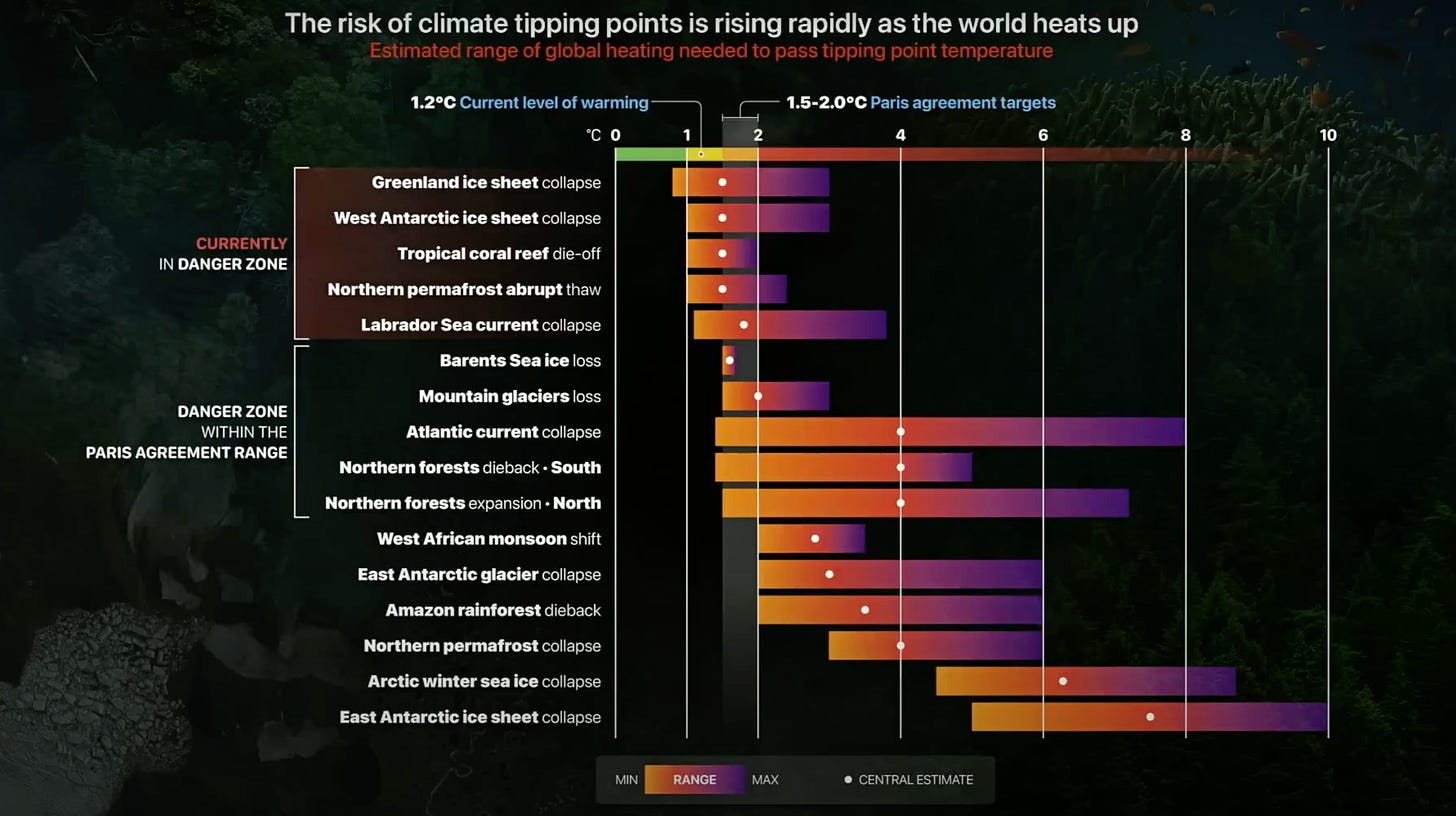

The paper provides three temperature thresholds at which tipping elements are expected to snowball: 1°C-3°C, 3°C-5°C and above 5°C. Issues like declining arctic summer sea-ice and the continued degradation of the Greenland Ice Sheet are known to be at risk within the initial threshold and are likely to fuel tipping points of the next threshold like the circulation of ocean currents, which in turn would intensify effects like the ongoing drought in the Amazon rainforest (where wildfires are currently burning at alarming rates).

At the core of their findings, the authors make clear it is virtually impossible to pinpoint with certainty the intricate connections of every system within the natural world. While increased CO2 may lead to increase plant growth in one area, hotter temperatures make it more difficult for leaves to photosynthesize, in turn lessening the ability for plants to draw carbon out of the atmosphere, all the while warming the soil which fuels respiration of the microbial life contained within, ultimately releasing more CO2 previously unaccounted for. It stands to reason then that the magnitude of these feedback loops depends a great deal on the rate at which climate change occurs. (Slower is better.)

Revisiting their initial questions:

Yes, considering the dynamics between systems, it is fair to conclude there is a threshold at which temperature rise will only continue to increase.

They recommend placing that threshold at a conservative 2°C, in line with the Paris target.

If Hothouse Earth were to become reality, the Earth System would “exceed limits of adaptation” leading to substantial degradation in “agricultural production, increased prices, and even more disparity between wealthy and poor countries.”

Addressing their final question is what led the authors to perhaps the most significant claim made by the paper: the need to recast humanity and our actions “as an integral, interacting component of a complex, adaptive Earth System.”

Stabilized Earth Pathway

The figure below is a powerful graphic. It could just as easily represent the plot of a choose-your-own adventure book, but instead it outlines two very real trajectories for the Earth System.

While agreeing on a term like the Anthropocene may seem to have little bearing on addressing the climate crisis, it actually represents a fundamental shift in how we perceive humanity, proving crucial to achieving a ‘Stabilized Earth.’

According to the authors, “Stabilized Earth is not an intrinsic state of the Earth System but rather, one in which humanity commits to a pathway of ongoing management of its relationship with the rest of the Earth System.”

The reason this call-to-action is so significant is that it represents a genuine shift in how we consider the relationship between humans and the nonhuman world. It demands we recognize our ability to effect change on this planet, both positive and negative, and that we begin to see humanity as stewards of the Earth System. Or, to borrow from Buckminster Fuller, as pilots aboard Spaceship Earth.

But recasting humanity is no small feat. Especially after thousands of years of culture that promoted the exact opposite. (Importantly though, this culture wasn’t a monolith.)

In order to do so, the authors make some rather radical claims for a scientific paper:

“Incremental linear changes to the present socioeconomic system are not enough to stabilize the Earth System. Widespread, rapid, and fundamental transformations will likely be required to reduce the risk of crossing the threshold and locking in the Hothouse Earth pathway; these include changes in behavior, technology and innovation, governance, and values.”

Read that quote once more.

It’s rare to find such statements about the status quo in a journal published by the National Academy of Sciences. And yet, there they are.

Incremental change will not be enough. Fundamental changes to our socioeconomic system are required. And to do so, we are likely going to be called on to make changes to how we govern, what we value, and how we live.

That being said, this is only called for if we want to avoid the Hothouse Earth.

Back to the Present

Jumping ahead some years since the publication of the “Hothouse Earth” paper, it’s disheartening to say there is little evidence of the sweeping changes it called for. But that’s not to say its message hasn’t been seeded elsewhere in the climate conversation.

This past August, professor of environmental science and global sustainability at Stockholm University and co-author of “Hothouse Earth”, Johan Rockström, gave a TED talk that undoubtedly sounded familiar to anyone already acquainted with the paper.

About halfway through, Rockström shows a slide on which we can see many of the same tipping points warned of years earlier — the primary difference being that all have now shifted even closer to the 2°C threshold.

Addressing the audience, Rockström distills its findings.

“What this tells us is the following. Five of these sixteen are likely to cross their tipping points already at 1.5°C. Just the two ice sheets hold ten meters of sea level rise which would be unstoppable on the long term.”

To be fair, Rockström acknowledges the uncertainty baked into these estimates. But not without also making one thing clear, “The more we understand the Earth system, the higher is the risk.”

Much of Rockström’s talk draws from another paper he co-authored and published in 2022 in the journal Science, “Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points.” In it, many of the same tipping points, thresholds and knock-on effects are discussed. But, interestingly, what is lacking are the mechanisms by which we might see these thresholds respected. Reinforcing all the more just how significant the call-to-action of the “Hothouse Earth” really was.

Change is gonna come?

Calls for transformative change are nothing new to society. What is new, however, is the threat of species suicide humanity faces as we debate whether or not to do something about it.

During an appearance on The Ezra Klein Show, when asked about our capacity to respond to this challenge, even Noam Chomsky, vocal advocate for many of the same radical changes suggested by the authors of “Hothouse Earth”, baulked at the idea of responding swiftly enough. “There’s no conceivable possibility of the kind of social change within the timescale that’s necessary.”

When asked more directly if our national and global political consortiums are capable of addressing the climate crisis, Chomsky offered a sobering take:

“There are two answers to that question. If the answer is no, we can say goodbye to each other. It’s as simple as that. We know how to do it, the methods are there, they’re feasible…Those of us who are willing to face reality know that it has to be done within the next couple of decades.”

“We have problems that are imminent, urgent. A couple of decades means urgent. This doesn’t mean everyone’s going to die in twenty years. It means processes will be set in motion that won’t be reversible. Then it’s just a matter of time before it’s all over.”

Much like the fork in the road previously mentioned, it would seem we are facing one of two scenarios. We can either meaningfully consider how we might adopt new methods of governance and economics, or continue business-as-usual. In either case, processes will be set in motion that will fundamentally change this planet and the future of humanity. Only one offers any hope of correcting course.